A stroke may be the first presentation of atrial fibrillation (AF). Approximately onefourth of ischemic stroke patients are newly diagnosed with AF1. The term, AF diagnosed after stroke (AFDAS) is used for both previously undetected, asymptomatic AF and poststroke AF2.

In acute ischemic stroke, structural brain lesions, especially those with cortical involvement, may lead to autonomic dysregulation and inflammation3. Although the pathophysiology has not been defined clearly, autonomic dysfunction and inflammation may play a role in the development of AF by lowering the cardiac arrhythmogenic threshold4. AF has been detected in more than half of the cases within 3 days after admission for ischemic stroke5. The mean time of AF diagnosis has ranged between 3 to 77 days after stroke. Meanwhile, AF detected earlier after the stroke has been suggested to be the consequence of the stroke, not the cause of the stroke2.

AFDAS patients are believed to have a more benign disease profile compared to patients with known AF (KAF). In a metaanalysis, it has been shown that AFDAS patients have a better vascular profile and lower comorbidities such as hypertension, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, coronary artery disease, heart failure, and previous stroke4. The duration of AF periods diagnosed after stroke is less than 30 seconds in approximately half of the patients, which implies that AF burden is lower in AFDAS patients6. Moreover, the ischemic recurrence of AFDAS is shown to be less, compared to patients with KAF before stroke7.

The aim of our study was to investigate the characteristics and mortality differences of the patients with strokes that preceded or occurred after the diagnosis of AF.

Methods

The investigation conformed to the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. All participants gave written informed consent. The study was approved by the ethics committee of Marmara University School of Medicine.

Study population

One hundred and thirtyfour patients presenting with acute ischemic stroke documented by cranial imaging were consecutively included in the study. The TOAST classification system was used to define the stroke subtypes8. National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) scores of patients were noted at the time of hospitalization. Patients with transient ischemic attacks (TIA) were not included in our study.

Patients were evaluated for the presence of comorbidities, including hypertension, hyperlipidemia, diabetes, and coronary artery disease. Blood samples for high sensitive (hs) Creactive protein (CRP), hscardiac troponin I (hscTnI), and Nterminal probrain natriuretic peptide (NTproBNP) levels were noted. All patients underwent a transthoracic echocardiographic study by a Philips Epic echocardiography device (Philips Medical Systems, Andover, MA, USA) by an experienced cardiologist within the first three days following acute ischemic stroke. Conventional echocardiographic measurements were performed by the recommendations of the American Society of Echocardiography guidelines9. LVEF was assessed by biplane Simpson’s method.

Electrocardiography (ECG) was obtained from each patient daily. Ambulatory ECG monitoring was performed in patients with sinus rhythm (SR) to explore AF or other arrhythmias within the first seven days following acute ischemic stroke. The ECG recordings were analyzed by an experienced cardiologist. Patients who had newly documented AF rhythm lasting more than 30 seconds in ambulatory ECG monitoring or daily 12lead ECG were classified as AFDAS, while patients who had known AF with anticoagulant therapy were grouped as KAF based on patientreported medical history and prior available medical records. AFs that were detected at the time of hospitalization that had not been diagnosed and treated before this ischemic stroke event, and that also occurred during the hospitalization period were also categorized as AFDAS.

Cranial images of the patients were reevaluated by experienced neurologists who were blind to patients’ characteristics to determine whether there was an insular cortex involvement.

All patients were followed for 1 year to obtain allcause mortality, cardiac mortality and neurogenic mortality.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed by statistical software (SPSS 21.0 for windows, Chicago, IL). The distribution of data was assessed by using onesample Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. Continuous data were expressed as mean ± SD while categorical data were expressed as numbers or percentages. Chisquared test was used for the comparison of categorical variables. Student’s ttest or ANOVA was used to compare the normally distributed continuous variables while the MannWhitney U test or KruskalWallis test was used to compare the nonparametric continuous variables. Post hoc analyses were performed using the Bonferroni test when an overall statistical significance was determined. Logistic regression analysis was performed to explore the predictors of allcause mortality. Statistical significance was accepted as a Pvalue less than 0.05.

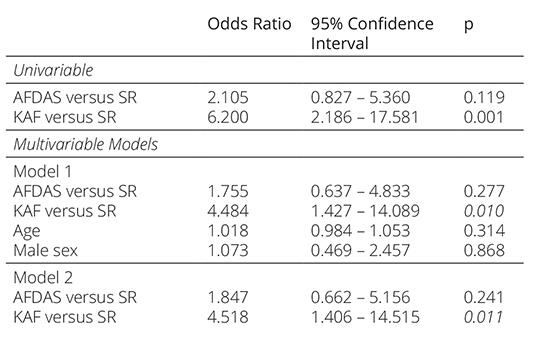

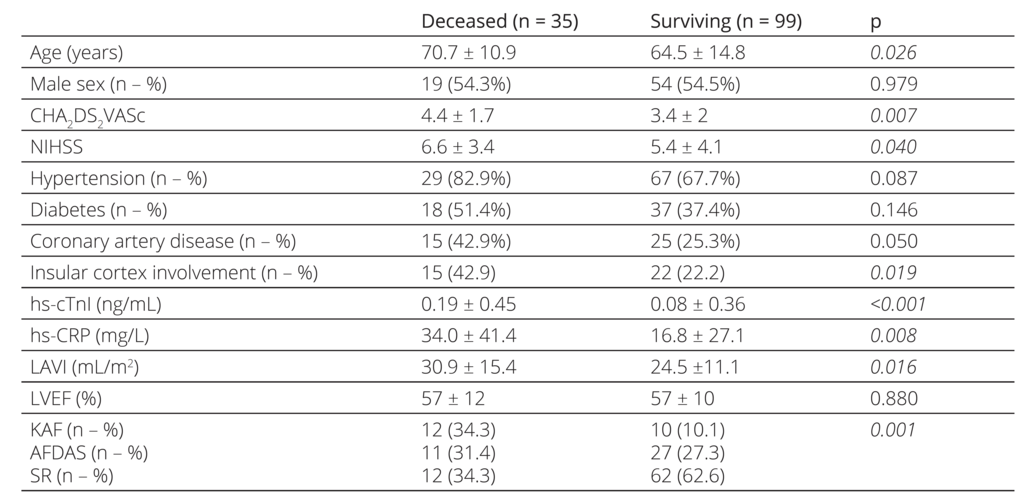

Table 1. The characteristics of the patients

KAF: known atrial fibrillation, AFDAS: atrial fibrillation diagnosed after stroke, SR: sinus rhythm, NIHSS: National Institutes of Health

Stroke Scale PostHoc analysis: * denotes statistical significance versus patients with sinus rhythm

Results

One hundred and thirtyfour consecutive ischemic stroke patients (66.1 ± 14.2 years old, n=73 male) were includ ed in the study. Twentytwo patients (16.4%) had KAF while AF was detected newly in 38 patients (28.4%), who were grouped as AFDAS. The remaining 74 patients (55.2%) had SR. The general characteristics of the pa tients according to cardiac rhythm are shown in Table 1. Patients with KAF and AFDAS were significantly older compared to the patients with SR, while there was no significant difference in age between KAF and AFDAS patients. KAF patients had higher CHA2DS2VASc scores and more insular cortex involvement than the SR group, while CHA2DS2VASc scores and insular cortex involve ment were similar between AFDAS and SR patients. There were no significant differences in the comorbidi ties and NIHSS scores among patients. Stroke patients with KAF and AFDAS were using betablockers more than SR patients.

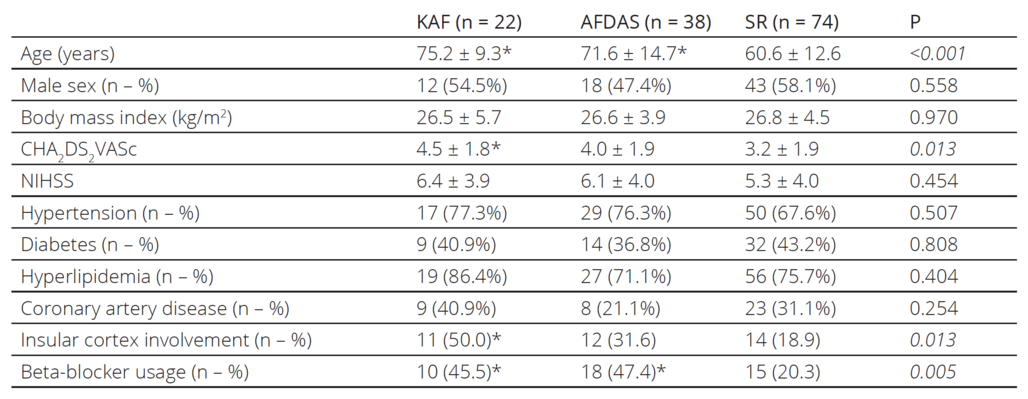

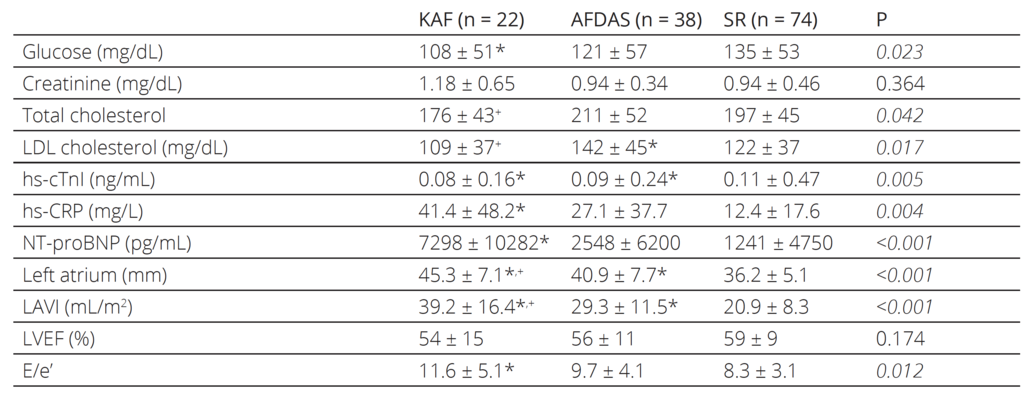

Table 2. The laboratory parameters and conventional transthoracic echocardiographic measures of the patients

KAF: known atrial fibrillation, AFDAS: atrial fibrillation diagnosed after stroke, SR: sinus rhythm, LDL: Low-density lipoprotein, hs-cTnI: High-sensitive cardiac Troponin I, hs-CRP: High-sensitive C-reactive protein, NT-proBNP: N terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide, LAVI: Left atrial volume index, LVEF: left ventricular ejection fraction, E/e’: the ratio of early diastolic mitral inflow velocity to early diastolic mitral annulus velocity

PostHoc analysis: * denotes statistical significance versus patients with sinus rhythm

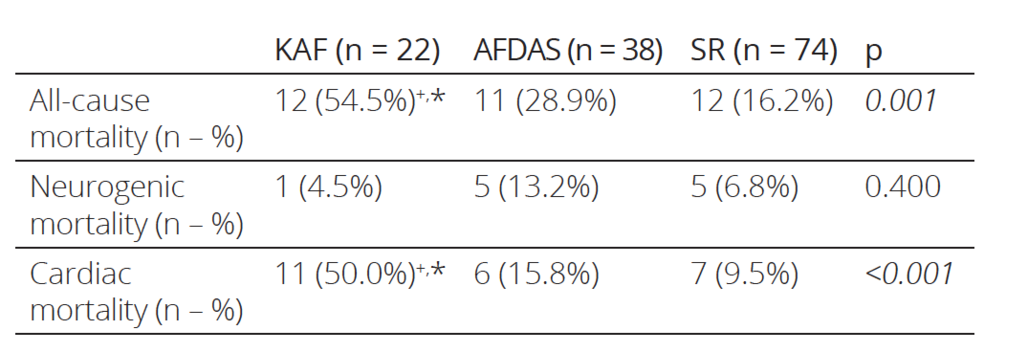

+ denotes statistical significance versus patients with atrial fibrillation diagnosed after a stroke

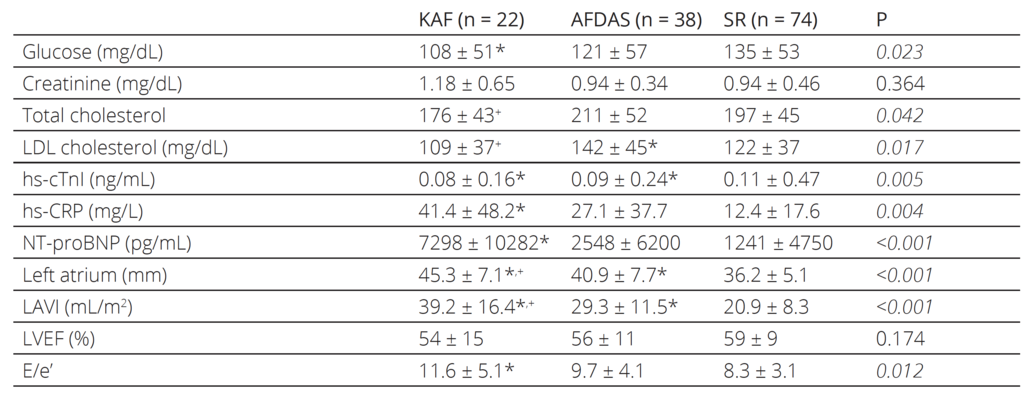

The laboratory and conventional echocardiographic parameters of the patients are listed in Table 2. hscTnI was elevated in all groups while the SR group had the highest mean. hsCRP levels were higher in KAF patients compared to patients with SR. While AFDAS patients had also higher hsCRP levels than patients with SR, the difference was not statistically signifi cant. KAF and AFDAS patients had sig nificantly larger left atriums compared to patients with SR. Although there were no significant differences in the left ventricu lar ejection fraction values of the patients, the KAF group had significantly higher NTproBNP and E/e’ compared to the SR group, while AFDAS and SR patients had similar NTproBNP and E/e’. During the oneyear followup period, 35 stroke patients died (12 patients in the KAF group, 11 in the AFDAS group, and 12 in the SR group). KAF patients had significantly higher allcause and cardiac mortality rates compared to both AFDAS patients and SR patients, while the AFDAS group had similar allcause and cardiac mortality rates to the SR group (Table 3).

Table 3. One-year mortality rates of the patients

KAF: known atrial fibrillation, AFDAS: atrial fibrillation diagnosed after stroke, SR: sinus rhythm

PostHoc analysis: * denotes statistical significance versus patients with sinus rhythm

+ denotes statistical significance versus patients with atrial fibrillation diagnosed after a stroke

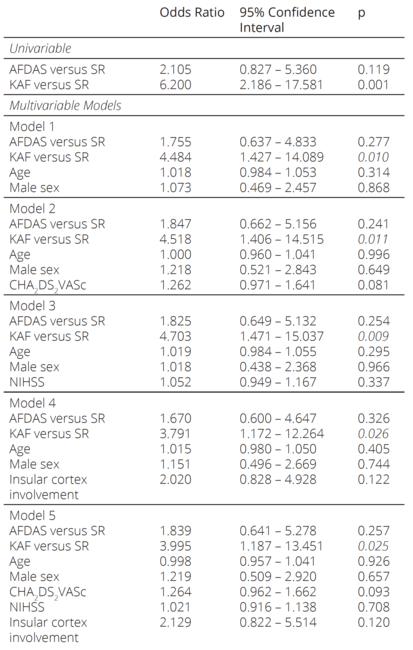

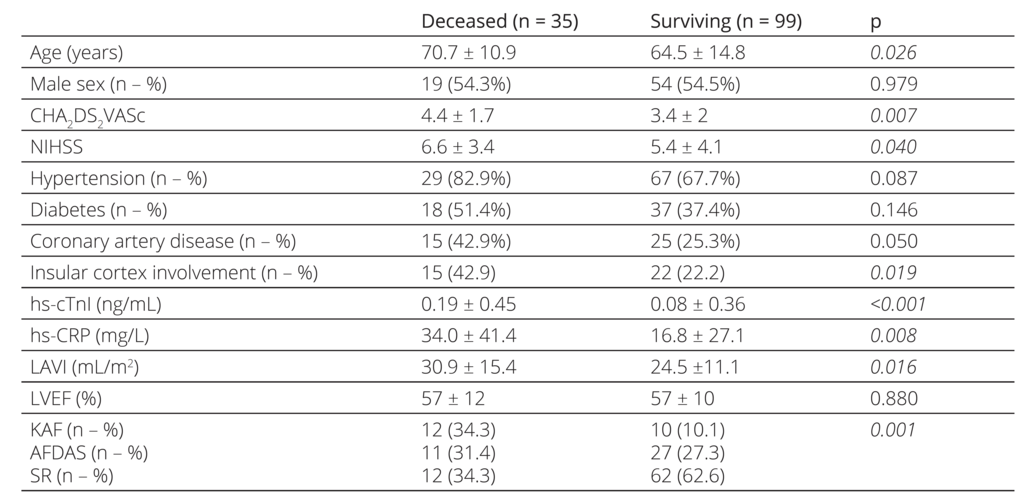

The characteristics, laboratory parameters, and con ventional transthoracic echocardiographic measures of stroke patients according to mortality status are shown in Table 4. These patients were older, had higher CHA2 DS2VASc and NIHSS scores, hscTnI, and hsCRP levels, with more insular cortex involvement, and larger left atrium.

Table 4. The characteristics of the patients according to all-cause mortality

NIHSS: National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale, hs-cTnI: High-sensitive cardiac Troponin I, hs-CRP: High-sensitive C-reactive protein, LAVI: Left atrial volume index, LVEF: left ventricular ejection fraction, KAF: known atrial fibrillation, AFDAS: atrial fibrillation diagnosed after stroke, SR: sinus rhythm

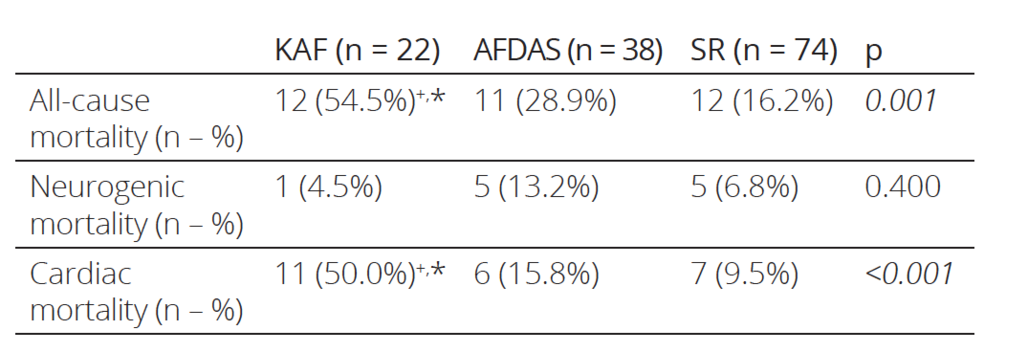

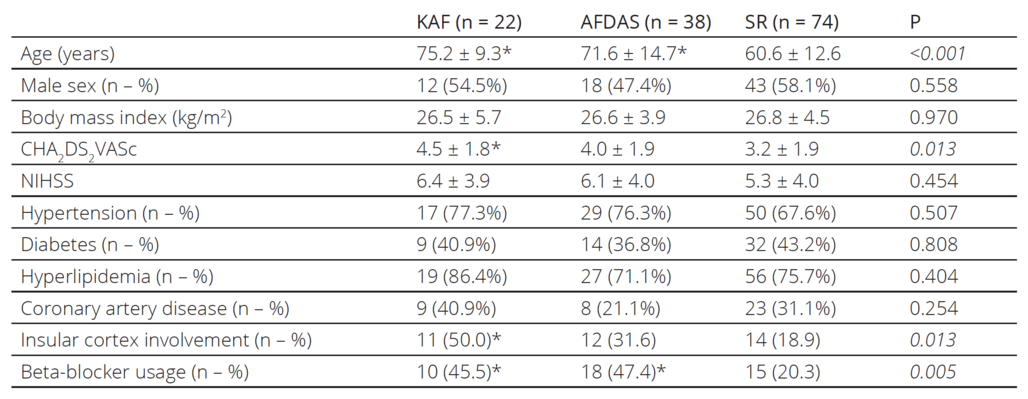

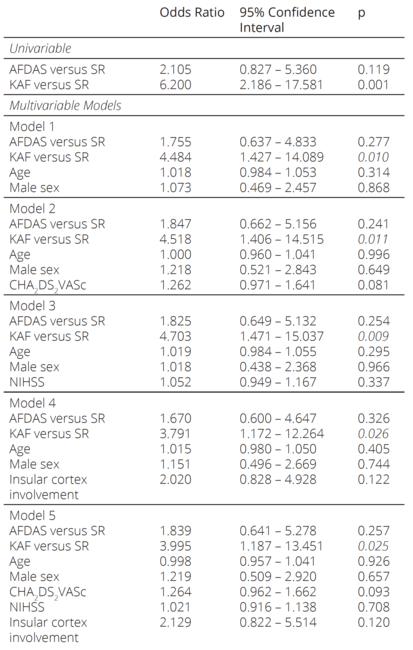

Univariable and multivariable logistic regression anal yses were modeled to explore the predictors of allcause of mortality (Table 5). Logistic regression analysis re vealed KAF as an independent predictor when adjusted by age, sex, CHA2DS2VASc and NIHSS scores, and in sular cortex involvement. While AFDAS increased the mortality risk compared to SR, the differences were not significant in univariable and multivariable models.

Table 5. Univariable and multivariable logistic regression analysis showing the predictors of all-cause mortality

KAF: known atrial fibrillation, AFDAS: atrial fibrillation diagnosed after stroke, SR: sinus rhythm, NIHSS: National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale

Discussion

In our study, we explored the characteristics and mortal ity differences between KAF and AFDAS patients. We found that while both AFDAS and KAF patients were significantly older than the patients with SR, CHA2 DS2VASc scores, insular cortex involvement, NIHSS scores, and comorbidities were similar between AFDAS and SR patients. Interestingly, only KAF was associated with mortality in both univariable and multivariable analysis, while AFDAS patients had similar mortality rates to SR patients.

Cardiovascular diseases are more common in both ischemic stroke and AF. However, cardiovascular dis ease and mortality rates are not the same in every AF patient. Underlying cardiovascular diseases and oneyear composite cardiovascular outcomes were observed to be higher in KAF patients than in AFDAS patients, but KAF was not found to be an independent predictor of outcomes10. Since comorbidities and structural heart dis ease are noted less in AFDAS patients, it is believed to be triggered by neurogenic mechanisms developed after stroke3, 11. Major factors such as autonomic dysfunction, increased catecholamine discharge, neurogenic cardiac injury, and systemic inflammation leading to atrial elec trical and structural remodeling after acute stroke may facilitate the occurrence and maintenance of AF2. In our study, coronary artery disease and other comorbidities such as hypertension, diabetes, and hyperlipidemia were found to be similar among groups.

There are conflicting results in the literature regarding the outcome of AFDAS. For example, in a study with 5year followup of stroke patients, the highest annual mortality was found in patients with newly diagnosed AF within the first 6 months after stroke12. Also, Yang XMet al showed that AFDAS patients had similar stroke re currence and mortality rates when compared to KAF but higher than SR13. In our study, mortality in the AFDAS group was found to be similar to sinus rhythm patients, which may be due to the more benign vascular profile of AFDAS as we predicted. In addition, little is known about the pathophysiology of AFDAS, but in recent stud ies, it is thought to have two subgroups, neurogenic and cardiogenic14. The cardiogenic AFDAS group with pre existing but newly diagnosed AF after stroke has atrial cardiopathy and structural heart disease15. In addition, in the neurogenic AFDAS group without structural heart disease, AF is thought to be triggered entirely by auto nomic and inflammatory mechanisms14. The heteroge neity of AFDAS may explain the difference in outcome between studies.

Although it has not been revealed yet, it is hypothe sized that large brain infarcts seen in moderate and se vere strokes cause more autonomic dysregulation and in flammation and therefore cause more AFDAS11, 15, 16. We measured stroke severity, which correlates with infarct size, but we couldn’t find any difference in NIHSS scores among the groups in our study. Studies about AFDAS showed a particularly remarkable involvement of the in sular cortex, which plays a role in the regulation of the autonomic nervous system3, 11. Although there are con flicting reports on which of the right and left hemisphere involvement increases sympathetic activity, increasing numbers of studies show that in insular cortex involvement the heart rate variability decrease and the risk of

AF increase significantly11, 17–19. In our study, significantly higher insular cortex involvement was found in KAF patients while there was no difference between AFDAS and SR groups in terms of insular cortex involvement.

In addition, autonomic dysfunction is thought to cause not only post-stroke AF but also myocardial injury: socalled neurogenic myocardial stunning (NSM)20. There are opinions that myocardial damage presenting with troponin elevation after stroke may be a predictor of AF21. In our study, hs-cTnI was found to be high in all groups, while the SR group had the highest mean and EF values were similar between groups. Since NSM is a reversible myocardial damage diagnosed with reduced EF, regional wall motion abnormality, ECG changes, and high troponin values, it is not possible to make a conclusion based on the data available in our study22, 23.

Approximately half of the ischemic strokes detected in the Penn Atrial Fibrillation Free study (PAFF) were detected within 6 months period before the diagnosis of AF. Most strokes occur on the day of diagnosis of AF and within the next 7 days24. In our study, approximately one-third of the patients were diagnosed with AFDAS, similarly in the first week. These patients had similar CHA2DS2VASc scores to patients with SR. However, the CHA2DS2VAS scores of KAF patients were higher than in the SR group. In another study investigating new AF with prolonged ECG monitoring more than one week after stroke, NIHSS and CHA2DS2VAS scores were found to be similar in groups with a previous diagnosis of AF and newly diagnosed AF25. It may be important on which day the diagnosis of AF is made after the stroke.

Limitations

First, a small sample size and a relatively short follow-up period are limitations of our study. Second, it has recently been revealed that AFDAS is a heterogeneous group and includes two different clinical entities as cardiogenic and neurogenic AFDAS. Due to the small number of AFDAS patients, we could not investigate the differences between these subgroups. Third, we excluded TIA because it was diagnosed with a subjective neurological evaluation, which might cause misdiagnosis of AFDAS. Fourth, AF might be underestimated as the patients did not undergo prolonged ambulatory ECG monitoring.

Conclusion

In summary, AFDAS patients were older but had similar insular cortex involvement, CHA2DS2VAS, and NIHSS score to SR patients; the insular cortex involvement and CHA2DS2VAS score were higher in the KAF group than in SR patients; AFDAS patients had similar mortality rates to SR patients; KAF patients had increased mortality compared to SR patients; mortality of the KAF group was independent of age, sex, insular cortex involvement, CHA2DS2VAS, and NIHSS scores.

AFDAS patients have similar CHA2DS2VAS scores and mortality rates to patients with sinus rhythm, which supports the hypothesis that AFDAS might be a relatively benign form of AF. However, having a KAF diagnosis before an ischemic stroke is an independent predictor of all-cause mortality.