Factors influencing the level of stigma in Parkinson’s disease in western Turkey

DEMIRYUREK Esra1, DEMIRYUREK Enes Bekir 2

SEPTEMBER 30, 2023

Clinical Neuroscience - 2023;76(9-10)

DOI: https://doi.org/10.18071/isz.76.0349

Journal Article

DEMIRYUREK Esra1, DEMIRYUREK Enes Bekir 2

SEPTEMBER 30, 2023

Clinical Neuroscience - 2023;76(9-10)

DOI: https://doi.org/10.18071/isz.76.0349

Journal Article

Szöveg nagyítása:

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is the second most commonneurodegenerative disease, affecting approximately 1% of people over the age of 601. Although the exact prevalence of PD in Turkey is not known, a study conducted in western Turkey found the prevalence to be 1.2%2. While motor symptoms such as tremor, rigidity, bradykinesia, and postural instability are traditionally associated with PD, non-motor symptoms, psychiatric issues, and social problems also contribute to the disability experienced by patients with PD1.

Stigmatization, characterized by condemnation, humiliation, devaluation, labeling, and social isolation, is a significant factor that negatively affects the quality of life and psychosocial well-being of people with chronic diseases3. Stigma strongly influences the social identity of stigmatized individuals4. In neuropsychiatric disorders, stigma can lead to avoidance of medical diagnosis, treatment, and support, reduced quality of life, and increased suicide rates4, 5. Stigma is a common concept among people with PD and should be carefully considered6, 7.

Previous studies have shown that more than half of patients with PD attempt to conceal their diagnosis8. In addition, highly stigmatized patients with PD may attempt to hide their clinical symptoms. Several factors contribute to the experience of stigma in patients with PD. Among the motor symptoms, the presence of a masked facial symptom affects social interactions and may lead to stigmatization, even by healthcare professionals, similar to the general population9. In addition, cardinal symptoms such as tremor, bradykinesia, and gait difficulties, as well as PD-specific difficulties such as medication fluctuations (i.e., motor off periods) and motor complications such as dyskinesia, have important psychosocial consequences such as stigma7, 9. Invisible stigma can lead to social isolation among people with PD, which may result in disability10.

Previous studies have reported a higher incidence of stigma in patients with PD with severe motor symptoms, significant impairment in activities of daily living, younger age, and higher levels of depression11–13. However, in addition to clinical manifestations, socio-cultural factors may also influence the stigma experienced by patients with PD. This study aims to assess the level of stigma and the factors influencing stigma among people with PD in western Turkey.

Methods

Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the local ethics committee. Informed consent was obtained from all participants enrolled in the study.

Participants

The study was conducted with 142 patients who were admitted to the neurology department of Kocaeli Acıbadem Hospital with PD between June 2022 and March 2023. Inclusion criteria were as follow: (1) patients with PD according to UK Brain Bank criteria; (2) participants aged ≥ 40 years; (3) patients with Hoehn and Yahr stage 4 and below. Exclusion criteria were: (1) patients with severe physical defects due to another disease; (2) mild, moderate, and severe cognitive problems by cognitive assessment. Cognitive assessment of patients was performed by clinical evaluation and the standardized Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) (patients with a cut-off score of 23 or less were considered to have dementia); (3) medication-refractory psychiatric disorders (major depression, psychosis, and mood disorders); (4) age < 40 years (diagnosed as juvenile PD); (5) Hoehn and Yahr stage 5 (bedridden due to PD and unable to participate in the surveys due to speech impairment); and (6) patients who refused to participate in the study.

Patients were evaluated in person, and the sociodemographic form, including age, gender, marital status, education level, and duration of PD, was completed by the same neurologist. The Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS part III) was used to assess motor symptoms of PD14. The disease stage was assessed using the Hoehn and Yahr scale. PD motor symptom subtype was calculated as the ratio of mean tremor to mean postural instability/gait difficulty (PIGD) symptoms. UPDRS Part III ratios greater than or equal to 1.5 were classified as tremor-dominant TD, whereas subjects with ratios less than or equal to 1.0 were classified as PIGD. Ratios between 1.0 and 1.5 were classified as mixed type15.

Depression was assessed with the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM-D). The HAM-D is a 17-item test that physicians can use to measure the severity of depression. It consists of 17 items about symptoms of depression experienced in the past week. Items related to difficulty falling asleep, waking up in the middle of the night, waking up early in the morning, somatic symptoms, genital symptoms, weakness, and insight are scored on a range of 0-2, and the other items are scored on a range of 0-4. The maximum score is 5316. Its Turkish reliability and validity study was conducted by Akdemir et al17.

Stigma was assessed using the Chronic Illness Anticipated Stigma Scale (CIASS) and the Stigma sub-scale of the 39-item Parkinson’s Disease Questionnaire (PDQ-39 Stigma sub-scale). The 5-point Likert-type Chronic Illness Anticipated Stigma Scale (CIASS) was developed by Earnshaw et al.3, and its Turkish validation study was conducted by Tunerir et al. in 201918. The scale consists of 3 sub-scales, including expected stigma from family and friends, colleagues, and healthcare professionals. The first 4 items of the scale aim to measure expected stigma from family and friends, the other 4 items aim to measure expected stigma from people at work, and the last 4 items aim to measure expected stigma from healthcare professionals. Each item is scored on a 5-point Likert scale.

The Parkinson’s Disease Questionnaire is a 39-item scale for assessing the quality of life in PD. Each item is scored from 0 to 4. Items 23-26 are used to assess stigma and are defined as the PDQ-39 Stigma sub-scale. The PDQ-39 stigma sub-scale is assessed with the following items: 23: Do you feel that you have to hide your PD from people? 24: Have you avoided situations where you have to eat or drink outside your home where others are present? 25: Have you felt embarrassed in public because of your PD? 26: Have you worried about other people’s reactions to you? Participants responded as (0: never, 4: always) and scores ranged from 0-1619. The Turkish validity study of this scale was conducted in 2018 by Kayapınar et al.20.

All raters were trained before the start of the study. The inter-rater concordance of all ratings was greater than 0.8.

Statistical analysis

The SPSS 21.0 program was used for the statistical analysis of the results obtained in the study. The normality of the distribution was tested using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test to determine the tests used in comparisons. Since the data were not normally distributed, non-parametric tests were used. Descriptive statistics, Cronbach’s alpha coefficient, and Spearman correlation analysis were used to evaluate the research data. SPSS was used to evaluate the results with a 95% confidence interval, and p<0.05 was accepted as statistically significant.

Results

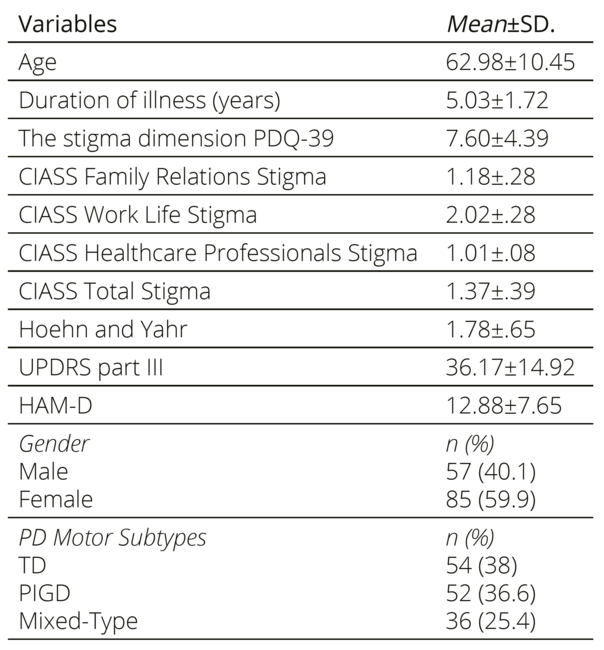

Table 1 shows that the mean age of the participants was 62.98±10.45 years, the mean disease duration was 5.03±1.72 years, 40.1% were male and 59.9% were female. The mean Hoehn and Yahr score was 1.78±0.65, the mean UPDRS part III score was 36.17±14.92, and the mean HAM-D score was 12.88±7.65. It was found that 38.0% of the patients had TD, 36.6% had PIGD, and 25.4% had mixed-type PD.

Table 1. General characteristics of patients with PD

Among the stigma scales, the mean PDQ-39 Stigma sub-scale score was 7.60±4.39, the mean CIASS Family Relations Stigma score was 1.18±0.28, the mean CIASS Work Life Stigma score was 2.02±0.96, the mean CIASS Healthcare Professionals Stigma score was 1.01±0.08, and the mean CIASS Total Stigma score was 1.37±0.39.

According to the results of Spearman correlation analysis, PDQ-39 Stigma sub-scale scores were positively correlated with Hoehn and Yahr at a low level (r=0.191, p=0.023) and positively correlated with CIASS Total Stigma and HAM-D at a high level (r=0.957, p=0.000). Highly significant negative correlations were found between age and PDQ-39 Stigma sub-scale (r=-0.700, p=0.000), CIASS Work Life Stigma (r=-0.749, p=0.000), and CIASS Total Stigma (r=-0.734, p=0.000), and moderate negative correlations were found with CIASS Family Relations Stigma (r=-0.465, p=0.000). Moderately significant negative correlations were found between disease duration and the PDQ-39 Stigma sub-scale (r=0.644, p=0.000), CIASS Family Relations Stigma (r=-0.430, p=0.000), CIASS Work Life Stigma (r=-0.663, p=0.000), and CIASS Total Stigma (r=-0.643, p=0.000).

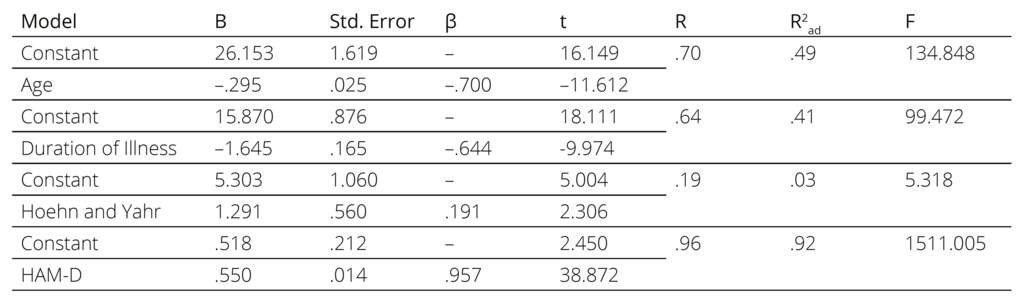

As a result of the simple linear regression analyses conducted to predict PDQ-39 Stigma sub-scale scores (shown in Table 2), it was observed that there is a decrease in PDQ-39 Stigma sub-scale scores with increasing age and disease duration and an increase in PDQ-39 Stigma sub-scale scores with increasing Hoehn and Yahr and HAM-D scores.

Table 2. Regression analysis results for predicting the stigma dimension PDQ-39 scores

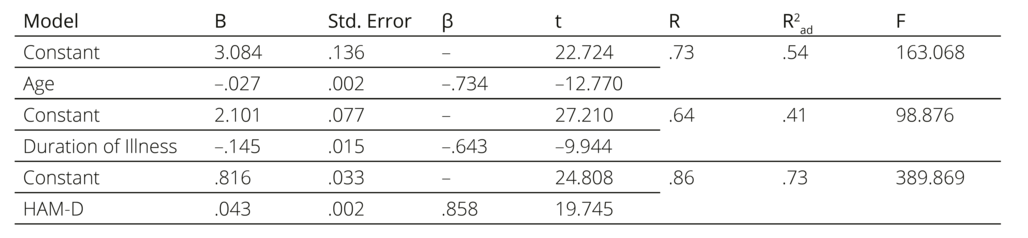

As a result of the simple linear regression analyses conducted to predict CIASS stigma scores, it was observed that there is a decrease in CIASS stigma scores as age and disease duration increase and an increase in CIASS stigma scores as HAM-D scores increase (Table 3).

Table 3. Regression analysis results for the prediction of CIASS stigma scores

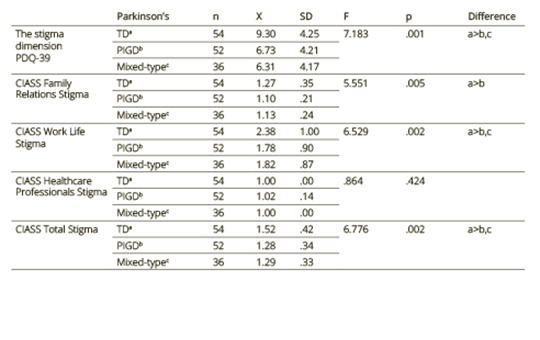

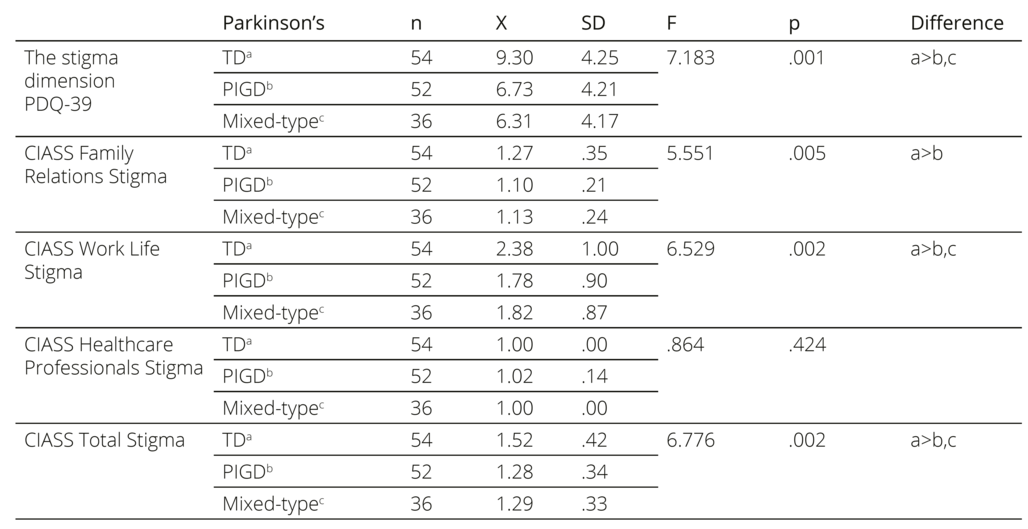

When the results of the “one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA)” were analyzed, it was found that there was a statistically significant difference in PDQ-39 Stigma (F=7.183, p=0. 001), CIASS Family Relations Stigma (F=5.551, p=0.005), CIASS Work Life Stigma (F=6.529, p=0.002), and CIASS Total Stigma (F=6.776, p=0.002) scores according to the subgroups of PD motor findings (Table 4). According to the post hoc (Scheffe) results performed to determine the origin of the difference, the mean scores of the patients with TD were found to be significantly higher than those of the PIGD and mixed-type patients in all variables in which there was a difference.

Table 4. Comparison results of stigma scales according to PD motor subtypes

Discussion

The present study revealed a higher prevalence of stigma among patients with the PD-TD motor subtype, younger age, shorter disease duration, greater disability, and the presence of depression. These findings suggest that effective management of motor symptoms, particularly tremor, and treatment of psychiatric issues, such as depression, could potentially reduce stigma.

Our study found a positive correlation between stigma scale scores and Hoehn and Yahr scores, indicating that stigma levels increase with greater disability as measured by the Hoehn and Yahr scale. However, in contrast to previous research, no significant correlation was found between UPDRS Part III parameters and stigma scores. We propose that this discrepancy may be due to the fact that stigma is influenced by the level of disability as assessed by the Hoehn and Yahr scale, whereas the UPDRS Part III assesses different motor symptoms that may vary depending on different cultural factors. When considering only the TD and PIGD scores, we found positive correlations between these scores and levels of stigma. However, when we conducted more in-depth analyses, it became clear that the TD score had a more pronounced influence on the level of stigma.

In this study, we found a positive correlation between the Hoehn and Yahr score and stigma levels. However, we also found that stigma levels increased as disease duration decreased. We hypothesize that this phenomenon may be due to the lack of a consistent correlation between disease duration and the Hoehn and Yahr score. It is possible that as disease duration increases, the propensity to accept and adapt to the condition increases, in contrast to the early stages. At the same time, the stigma levels observed in younger individuals may be due to the shorter disease duration.

PD-specific motor subscores may have a direct and significant impact on stigma. Resting tremor, bradykinesia, and postural and gait disturbances attract public attention, lead to changes in body image, and evoke in patients feelings of shame, embarrassment, and isolation21, 22.

In addition, Hermanns et al. reported that the masked face symptom, which results in impaired speech and difficulty with nonverbal communication in participants with PD, leads to social isolation and stigma9. Another multicenter study conducted in the USA and Taiwan reported that the masked face symptom caused prejudice against patients with PD even among healthcare professionals, but this prejudice was more prevalent in the USA than in Taiwan due to cultural factors10. In our study, similar to the study conducted in China13, tremor in particular was found to be important in the stigmatization of patients. In the Chinese study, when the authors interviewed patients with Parkinson’s disease, they found that patients increased the doses of the medications they used to stop tremors and that the reason of their desire to stop tremors was to break other people’s prejudices against them. In addition, we suggest that the higher stigma scores observed in PD patients with TD compared to PD patients with PIGD may be due to the inability of patients to reduce their tremors. In contrast, PIGD patients may be adept at concealing their symptoms (e.g., by adopting a seated position during periods of increased stability and gait difficulties), resulting in lower stigma. Nonetheless, postural instability/gait difficulties can potentially lead to an increased risk of falls and traumatic injuries, which indirectly contribute to stigma. In our study, both stigma scale scores increased in parallel with Hoehn and Yahr scores. Conversely, no positive correlation was found between UPDRS Part III scores and stigma scores, which differs from findings in other studies. We hypothesize that this discrepancy is due to the increase in stigma relative to PD-related disability as quantified by the Hoehn and Yahr scale. On the contrary, the UPDRS Part III parameters encompass a variety of motor manifestations, and their diversity varies according to cultural factors.

Depression causes social withdrawal in addition to motor symptoms such as tremors, gait disturbances, and falls in patients with PD. Depressed patients experience more shame, hopelessness, and anxiety due to PD, which directly and indirectly increases perceived stigma in patients11–13. Salazar et al. reported that depression was an important predictor of stigma in patients with PD, and the level of depression significantly affected stigma and activities of daily living11. Another study conducted in China reported that the level of stigma score increased with increasing HAM-D score in patients with PD13. A study conducted in the United Kingdom reported that about half of patients with PD retired early within 5 years of disease onset, causing economic crisis and psychological pressure23. Consistent with the literature, our study found that the level of stigma increased as the level of depression increased and that the level of depression was a predictor of stigma in patients with PD. The change in social roles and social interactions in patients with PD may affect the quality of life and psychology of these patients and their families24. Moreover, as stigma is a very important socio-cultural factor, it is important to recognize the social significance of PD and PD-related symptoms, and for this reason, we anticipate that targeted treatment of depression in patients with PD is important to reduce stigma.

Our study found a positive association between younger age and increased stigma among people with PD. The experience of being diagnosed with a neurodegenerative disease at a relatively young age may be qualitatively different from that of being diagnosed at an older age, as it may significantly affect one’s familial, social, and occupational self-perceptions and expectations25, 26. In addition, the uncertainty surrounding the ability to slow or halt the progression of PD in younger individuals may contribute to psychological distress, while the prolonged duration of the disease may impose limitations on social and daily activities, potentially leading to social isolation27.

Several limitations of this study should be acknowledged. First, the cross-sectional nature of the study design precludes the establishment of causal relationships between the independent variables and outcomes. Second, the assessment of the quality of life was limited to the stigma-related items of the PDQ scale and did not include a comprehensive assessment of the overall quality of life. Third, the study did not investigate other social determinants such as income, education, and occupation. Finally, the sample size was limited to a single hospital and did not include severely affected patients, which limits the generalizability of the findings.

In conclusion, this study assessed levels of stigma against Parkinson’s patients with different motor subtypes and at different stages of the disease. Our study showed that stigma is associated with disease progression, disease duration, and depression in patients with PD in western Turkey. We anticipate that the implementation of multiple approaches will reduce stigma and improve the quality of life of people with PD as a result of studies that evaluate the effects of different predictors with more centers, more patients, and participants from different regions.

Clinical Neuroscience

In this study, we analyzed the effect of oral and oral + intravenous Alpha-lipoic acid (ALA) treatment on pain level and physical examination findings in patients diagnosed with carpal tunnel syndrome (CTS). A total of 115 patients patricipated in the study. 40 patients were treated with oral ALA after iv. ALA the¬rapy, 35 patients received only oral ALA treatment and 40 patients did not receive any medication.

Clinical Neuroscience

Ciprofloxacin (CIP) is a broad-spectrum antibiotic widely used in clinical practice to treat musculoskeletal infections. Fluoroquinolone-induced neurotoxic adverse events have been reported in a few case reports, all the preclinical studies on its neuropsychiatric side effects involved only healthy animals. This study firstly investigated the behavioral effects of CIP in an osteoarthritis rat model with joint destruction and pain.

Clinical Neuroscience

Gliomas are the most common primary malignant central nervous system tumors in adults, exhibiting a poor prognosis. Indoleamine 2, 3-dioxygenase-1 has important functions in cancer immunotherapy due to its role in escaping cancer cells from the immune system. In this study we purposed to evaluate the correlation between IDO-1 expression and clinicopathological parameters in gliomas, and whether IDO-1 can be a prognostic marker.

Clinical Neuroscience

[Migraine as a common primary headache disorder has a significant negative effect on quality of life of the patients. Its pharmacotreatment includes acute and preventative therapies. Based on the shared therapeutic guideline of the European Headache Federation and the European Academy of Neurology for acute migraine treatment a combination of triptans and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs is recommended for acute migraine treatment in triptan-nonresponders. In this short review we summarized the results of the randomized controlled clinical trials evaluating the effectiveness and safety of sumatriptan (85 mg)/naproxen sodium (500 mg) fix-dose combination. It was revealed that the fix-dose combination was better than placebo for the primary outcomes of exemption of pain and headache relief at 2 hours. Furthermore the combination showed beneficial effect on accompanying symptoms of migraine attack (i.e. nausea, photo- and phonophobia). Adverse events were mild or moderate in severity and rarely led to withdrawal of the drug.

It can be concluded that sumatriptan (85 mg)/naproxen sodium (500 mg) fix-dose combination is effective, safe and well-tolerated in the acute treatment of migraine. ]

Clinical Neuroscience

[Epilepsy is one of the most common neurological disorders. Therapeutic success shows high variability between patients, at least 20-30% of the cases are drug-resistant. It can highly affect the social status, interpersonal relationships, mental health and the overall quality of life of those affected.

Although several studies can be found on the psychiatric diseases associated with epilepsy, only a few researches focus on the occurrence of personality disorders accompanying the latter. The aim of this review is to help clinicians to recognize the signs of personality disorders and to investigate their connection and interaction with epilepsy in the light of current experiences.

The researches reviewed in this study confirm that personality disorders and pathological personality traits are common in certain types of epilepsy and they affect many areas of patients’ lives. These studies draw attention to the importance of a multidisciplinary approach to this neurological disorder and to provide suggestions about the available help options. Considering the high frequency of epilepsy-related pathological personality traits that can have a great impact on the therapeutic cooperation and on the patients’ quality of life, it important that the neurologist recognizes early the signs of the patient’s psychological impairment. Thus they can get involved in organizing the support of both the patient and their environment by including psychiatrists, psychologists, social and self-help associations.

As interdisciplinary studies show, epilepsy is a complex disease and besides trying to treat the seizures, it is also important to manage the patient’s psychological and social situation. Cooperation, treatment response and quality of life altogether can be significantly improved if our focus is on guiding the patient through the possibilities of assistance by seeing the complexity and the difficulties of their situation.]

Clinical Neuroscience

Parkinson’s disease is a progressive neurodegenerative disease characterized by motor and non-motor symptoms. Levodopa is the most effective drug in the symptomatic treatment of the disease. Dopamine receptor agonists provide sustained dopamin-ergic stimulation and have been found to delay the initiation of levodopa treatment and reduce the frequency of various motor complications due to the long-term use of levodopa. The primary aim of this study was to compare the efficacy of potent nonergoline dopamine agonists pramipexole and ropinirole in both “dopamine agonist monotherapy group” and “levodopa add-on therapy group” in Parkinson’s disease. The secondary aims were to evaluate the effects of these agents on depression and the safety of pramipexole and ropinirole. A total of 44 patients aged between 36 and 80 years who were presented to the neurology clinic at Ministry of Health Diskapi Yildirim Beyazit Training and Research Hospital, Ankara, Turkey and were diagnosed with idiopathic Parkinson’s disease, were included into this randomized parallel-group clinical study. Dopamine agonist monotherapy and levodopa add-on therapy patients were randomized into two groups to receive either pramipexole or ropinirole. The maximum daily dosages of pramipexole and ropinirole were 4.5 mg and 24 mg respectively. Patients were followed for 6 months and changes on Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale, Clinical Global Impression-severity of illness, Clinical Global Impression-improvement, Beck Depression Inventory scores, and additionally in advanced stages, changes in levodopa dosages were evaluated. Drug associated side effects were noted and compared. In dopamine agonist monotherapy group all of the subsections and total scores of Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale and Clinical Global Impression-severity of illness of the pramipexole subgroup showed significant improvement particularly at the end of the sixth month. In the pramipexole subgroup of levodopa add-on therapy group, there were significant improvements on Clinical Global Impression-severity of illness and Beck Depression Inventory scores, but we found significant improvement on Clinical Global Impression-severity of illness score at the end of the sixth month in ropinirole subgroup too. The efficacy of pramipexole and ropinirole as antiparkinsonian drugs for monotherapy and levodopa add-on therapy in Parkinson’s disease and their effects on motor complications when used with levodopa treatment for add-on therapy have been demonstrated in several previous studies. This study supports the effectiveness and safety of pramipexole and ropinirole in the monotherapy and levodopa add-on therapy in the treatment of Parkinson’s disease.

Clinical Neuroscience

[COVID-19 has made providing in-person care difficult. In most countries, including Hungary, telemedicine has partly served as a resolution for this issue. Our purpose was to explore the effects of COVID-19 on neurological care, the knowledge of neurology specialists on telemedicine, and the present state of telecare in Hungary, with a special focus on Parkinson’s disease (PD). Between July and October 2021, a nationwide online survey was conducted among actively practicing Hungarian neurology specialists who were managing patients with PD. A total of 104 neurologists were surveyed. All levels of care were evaluated in both publicly funded and private healthcare. Both time weekly spent on outpatient specialty consultation and the number of patients with PD seen weekly significantly decreased in public healthcare, while remained almost unchanged in private care (p<0.001); higher portion of patients were able to receive in-person care in private care (78.8% vs. 90.8%, p<0.001). In telecare, prescribing medicines has already been performed by the most (n=103, 99%). Electronic messages were the most widely known telemedicine tools (n=98, 94.2%), while phone call has already been used by most neurologists (n=95, 91.3%). Video-based consultation has been more widely used in private than public care (30.1% vs. 15.5%, p=0.001). Teleprocedures were considered most suitable for monitoring progression and symptoms of Parkinson’s disease and evaluating the need for adjustments to antiparkinsonian pharmacotherapy. COVID-19 has had a major impact on the care of patients with PD in Hungary. Telemedicine has mitigated these detrimental effects; however, further developments could make it an even more reliable component of care.]

Clinical Neuroscience

Background and purpose – To evaluate the efficacy of the combined therapy of bilateral subthalamic nucleus deep brain stimulation (STN-DBS) and dopaminergic medication on balance and mobility in patients with Parkinson’s disease (PD).

Clinical Neuroscience

This study aims to investigate the validity and reliability of the Turkish Version of the 39-item Parkinson Disease Questionnaire. A total of 100 patients with Parkinson’s disease who were admitted to the outpatient neurology clinic in Koc University and Istanbul University were enrolled. 39- item Parkinson Disease Questionnaire, Parkinson Disease Quality of Life Questionnaire, Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale, Hoehn-Yahr Scale, and Short Form Health Survey-36 were administered to all participants.

Clinical Neuroscience

The study aims to investigate the relationship between the progression of idiopathic Parkinson’s disease (IPD) and retinal morphology. The study was carried out with 23 patients diagnosed with early-stage IPD (phases 1 and 2 of the Hoehn and Yahr scale) and 30 age-matched healthy controls. All patients were followed up at least two years, with 6-month intervals (initial, 6th month, 12th month, 18th month, and 24th month), and detailed neurological and ophthalmic examinations were performed at each follow-up. Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale part III (UPDRS Part III) scores, Hoehn and Yahr (H&Y) scores, best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA), intraocular pressure (IOP) measurement, central macular thickness (CMT) and retinal nerve fiber layer (RNFL) thickness were analyzed at each visit. The average age of the IPD and control groups was 43.96 ± 4.88 years, 44.53 ± 0.83 years, respectively. The mean duration of the disease in the IPD group was 7.48 ± 5.10 months at the start of the study (range 0-16). There was no statistically significant difference in BCVA and IOP values between the two groups during the two-year follow-up period (p> 0.05, p> 0.05, respectively). Average and superior quadrant RNFL thicknesses were statistically different between the two groups at 24 months and there was no significant difference between other visits (p=0.025, p=0.034, p> 0.05, respectively). There was no statistically significant difference in CMT between the two groups during the follow-up period (p> 0.05). Average and superior quadrant RNFL thicknesses were significantly thinning with the progression of IPD.

1.

Clinical Neuroscience

[Headache registry in Szeged: Experiences regarding to migraine patients]2.

Clinical Neuroscience

[The new target population of stroke awareness campaign: Kindergarten students ]3.

Clinical Neuroscience

Is there any difference in mortality rates of atrial fibrillation detected before or after ischemic stroke?4.

Clinical Neuroscience

Factors influencing the level of stigma in Parkinson’s disease in western Turkey5.

Clinical Neuroscience

[The effects of demographic and clinical factors on the severity of poststroke aphasia]1.

2.

Clinical Oncology

[Pancreatic cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guideline for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up]3.

Clinical Oncology

[Pharmacovigilance landscape – Lessons from the past and opportunities for future]4.

5.